The incendiary, unrelenting and ribald nature of Irish folk wit and banter at its level best is an awesome beast to behold. Some years ago I was walking around the Cathedral Quarter of Belfast and across Writer's Square facing The John Hewitt Bar on Donegall Street. Amongst the literary wordage enshrined on the ground there is Joseph Tomelty's scathing observation on life, fate and drudgery - What a bloody awful place for a man of imagination.

Tomelty was a Northern Irish actor born in Portaferry on County Down's Strangford Lough shore who starred in the movies Moby Dick and A Kid For Two Farthings. He was also the author of many works including the novel Red Is The Port Light, the prototype folk horror play All Soul's Night and the classic Ulster radio comedy The McCooeys which provided the comic actor James Young with his commercial breakthrough. He was also the former father-in-law of Sting.

I was reading about Tomelty this weekend with regard to Carol Reed's classic Odd Man Out film of 1947 in which he had a minor role. This feature starred James Mason as an IRA man on the run in Belfast after a robbery at a linen mill and included location shots from the Crumlin Road and the Ligoniel district in the north of the city. It garnered attention from contemporary censors because of the violent content but was certainly a brave attempt at that time to analyse the complex dynamics of bloody political conflict in Ireland.

Another example of wonderfully surreal Hibernian word association that stopped me in my tracks in the past were the comments of writer Declan Lynch in the 2014 Return of the Dancehall Sweethearts documentary about Irish folk rock legends Horslips. Lynch noting how the five-piece group "took the constituent parts of what it meant to be Irish and they put them back together in a way that wasn't crap".

Everything you ever want to know about Horslips can be found in the 2013 official biography Tall Tales by Mark Cunningham (and also Mark J Prendergast's long out-of-print Irish Rock: Roots, Personalities, Directions) but it is worth reiterating here the truly unique role they played within the cultural life of Seventies Ireland. This not only in regard to their native Irish Republic as a national musical act that had the capacity and talent to have been one of the biggest commercial draws on the globe but as one of the few major rock artists to continue to play in Ulster during the Troubles. In fact Horslips' last ever live performance was at the Whitla Hall at Queens University Belfast in May 1980.

Of the nine studio albums released between 1972 and 1979 the two most well-recalled after their groundbreaking Happy To Meet, Sorry To Part debut would be the fusion of hard rock, traditional folk and Celtic mythological narrative on The Tain (1973) and The Book of Invasions (1976) - these based respectively on Ulster's tenth century Cattle Raid of Cooley legend and a twelfth century chronicle of pre-Christian colonisations of Ireland.

Dancehall Sweethearts (1975) and The Unfortunate Cup of Tea (1976) have some leanings towards more prog and poppier material alike but the former in particular has dated very well. Two later albums based on Ireland's experience of emigration to the New World - Aliens (1977) and The Man Who Built America (1978) - successfully pulled off a harder American rock approach which (like Big Country's The Buffalo Skinners) really warranted a much bigger and appreciative audience. However in light of the distance this took them from the folk base, the final album Short Stories, Tall Tales was to be the weakest of the studio albums though does contain the utterly sublime Rescue Me.

The Seventies discography is rounded off by the massively underrated Drive The Cold Winter Away acoustic folk collection from 1975, two live albums and an early compilation of rarities including two quirky Beatles tributes from "Lipstick"and the brilliant Motorway Madness. Horslips reformed for an unplugged live recording Roll Back in 2004 and in 2010 and 2011 further live albums were lifted from concerts at the O2 Arena Dublin and the Ulster Hall in Belfast.

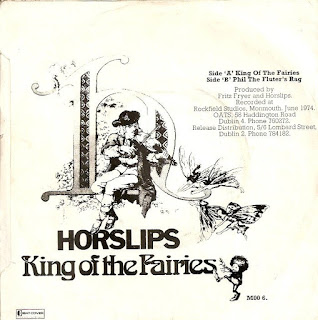

The five individual members of the group were born in Dublin, Limerick, Kells County Meath, Ardboe by Lough Neagh in Northern Ireland and Middlesborough on Tyne and Wear. All their original albums were released in Ireland on their own Oats label with artwork designed by the group themselves - they also remained domestically resident in Ireland throughout the Seventies.

Horslips' commercial success may have been overshadowed by Thin Lizzy on an international scale but it is important to remember that the first LP release was the fastest selling album in Ireland in eight years, Dearg Doom from The Tain was a German number one single and The Book of Invasions reached number 39 on the UK album charts in the middle of a mainland IRA bombing campaign which may have possibly muddied some very clever people's marketing strategies. The passion and fire of their live performances in the British Isles, mainland Europe and North America are still talked about today with awe, respect and deep appreciation.

The King of the Fairies, Dearg Doom (as performed on the BBC Old Grey Whistle Test) and Trouble With a Capital T remain fairly well known to informed fans of classic rock music today but do take time to forge around Horslips back catalogue if you can. Go beyond the generic Celtic rock categorising and the draining bloody Jethro Tull comparisons to their fantastic second single Green Gravel, the wonderful instrumentals Ace and Deuce and We Bring the Summer With Us, to the great lost Seventies rock classic Sunburst, Self Defence from The Unfortunate Cup of Tea, the b-sides The High Reel and When The Night Comes, to New York Wakes off Aliens, The Man Who Built America's title track and particularly the entirety of the winter folk collection.

Without exaggeration Horslips stand alongside George Best in modern Irish social history as utterly unique creative talents who embodied so much of the soul and pride of the country during days of grim political turmoil, economic stagnation and shameful cultural division.